-No Forest No Happiness-

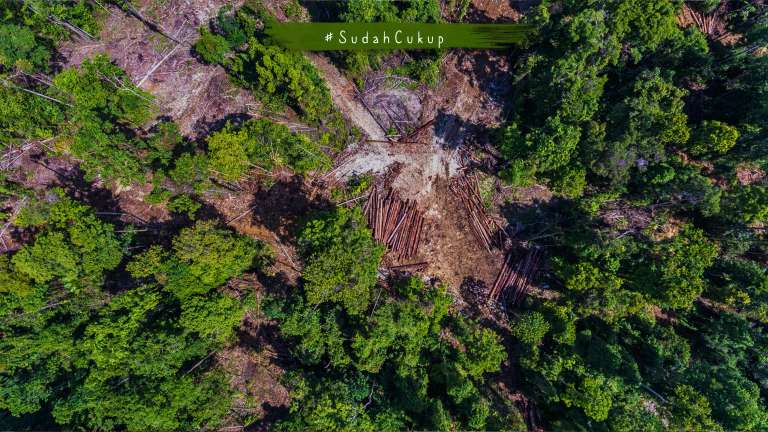

The word “Enough” is representative of the conditions and various kinds of forest problems in Indonesia today. Where, deforestation (forest loss) continues at an ever increasing rate. In the period 2009-2013, natural forest loss in Indonesia was 1.13 million hectares / year, or the equivalent of 3 times the area of a football field per minute. The next period, namely 2013-2017, the rate of deforestation has increased to 1.4 million hectares / year or the equivalent of 4 times the area of a football field per minute.

One of the main problems in natural resource management is the control of forests and land which is only controlled by a handful of people. Human greed in capturing natural resources in Indonesia is considered sufficient considering that there has been a lot of excess forest and land given to such a handful of people. In fact, areas that have been controlled by corporate licenses have proven ineffective in improving the welfare of the community. One of the highlights in encouraging state revenue from the natural resource sector is programs in each sector that tend to be expansionary. Whereas the real problem is productivity, not lack of land. A case in point is oil palm production, in Indonesia every one hectare of oil palm can only produce 3 tons of Fresh Fruit Bunches (FFB), while in Malaysia each hectare is capable of producing 12 tons. In fact, the area of oil palm plantations continues to increase at the expense of remaining natural forests.

Knowledge of the causes of flooding due to dwindling forests was instilled from an early age. Sadly, this simple understanding and logic is rarely contained and is often forgotten in every policy and implementation, especially in flood mitigation and mitigation policies that have never been on target on the main problem. In fact, high rainfall is often used as a “sacrifice” as a cause of flooding.It seems that the policies in flood mitigation have never seen that reduced forest cover is the main cause of flood disasters. The correlation between forest cover and BNPB’s flood risk ratio shows that the lower the ratio of forest cover in an area results in a higher potential for flooding to occur. Vice versa, areas that have a high forest cover ratio have a low flood risk value.

The KPK stated that the most potential for corruption lies in the Natural Resources sector. The KPK’s National Movement to Save Natural Resources (GNPSDA) has identified dozens of corruption-prone spots in the natural resource management sector. One of the most vulnerable points is the bribery and gratuity that occurs in every stage of the permit. Until 2017 alone, there were around 739 people from various backgrounds being the target of investigations and investigations into natural resource corruption cases. In addition, other facts also show that more than 70% of regional heads during the elections were supported by natural resource-based corporations, with compensation for easy business permits. So, it is not surprising that many regional heads are caught in corruption cases. In terms of losses, by 2014 the KPK had handled 16 cases of corruption related to natural resource (SDA) licensing with state losses reaching Rp 3.5 trillion. This fantastic number shows the existence of buying and selling permits in our current bureaucracy. Especially in the natural resource sector.

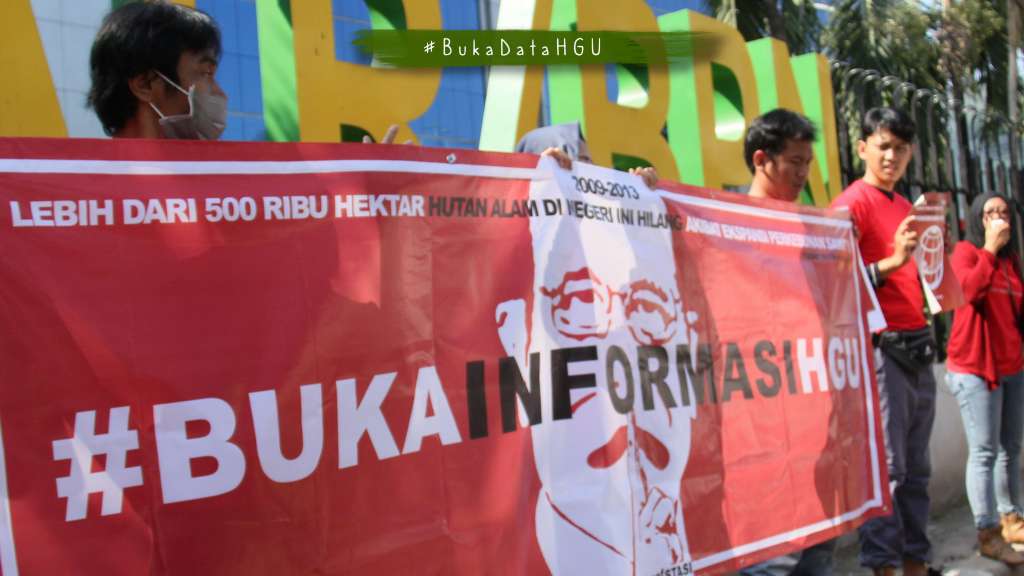

Openness and transparency in natural resource management is one of the keys to improving forest and land governance in Indonesia. The management of natural resources which tends to be closed has created an opening for corrupt practices and abuse of power. Management of natural resources which is carried out openly will also open up opportunities for the community to participate in natural resource management. Whether it’s the planning stage, protection, and also public supervision in every natural resource management activity. Examples of cases such as permit Maps, AMDAL, HGU, and so on, which in terms of regulations and legal provisions have been declared as open documents but in practice they are still closed. Even actions against the law are often carried out by the government itself. An example is the statements of government officials who refuse to disclose HGU data for oil palm plantations even though they have been decided as open documents by the Supreme Court.

Injustice and inequality in the distribution of forest and land management permits in Indonesia are issues that have not been resolved to date. As a result, social conflicts between communities and corporations almost always appear in every forest and land use activity carried out by large (private) corporations. In fact, it tends to increase from year to year. From 161 conflicts in 2013, it increased to 1,084 cases in 2017. The Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning also said that the land tenure ratio in Indonesia is close to 0.58. This means that only about 1% of the population controls 59% of agrarian resources, land and space. A similar sentiment was also expressed by the Minister of Environment and Forestry, Siti Nurbaya. He stated that most of the forest is controlled by private companies.

Many people prefer silence out of ignorance. So it is important to flood the community with information related to the condition of forests in Indonesia. With that, we are able to invite the community to not just be silent and participate in voicing that #SudahCough Indonesia’s forests are cut. #Already quite an area of Indonesian forests that were converted and sacrificed, #Already enough corruption in the natural resource sector, #Already enough forest management that is managed secretly and #Already enough, the Indonesian people remain silent over the injustices that occur.

The western region of Indonesia (Java and Sumatra Island) has started to run out of natural forests. It only leaves a small part of the upstream area (usually in the form of protected / conservation areas) and is the last bastion of the life system in the two regions. It is recorded that up to 2017, the land in the Java region only leaves around 900 thousand hectares of natural forest or 5.5% of the total land area. Meanwhile, Sumatra leaves 10.4 million hectares or 22% of the total land area. With the above conditions, it is not surprising that floods and landslides often hit the two regions. Unlike Java and Sumatra, Kalimantan is a region where 46.8% of its land area is still covered by natural forests. However, these natural forests continue to be lost even at the fastest rate compared to other regions in Indonesia. In terms of control, 60% of the land in Kalimantan has been controlled by natural resource utilization permits such as HPH, HTI, oil palm plantations and mining. So it is not surprising, with the condition of Kalimantan which loses 528 thousand hectares of natural forest every year, in 2064 the natural forests in Kalimantan will be exhausted.

Areas that still have forests will continue to be exploited up to the limit of the ability to cut forests, not the limit of how much forest can be cut. The exploitation that is carried out no longer considers the carrying capacity and carrying capacity of an area. The pattern of deforestation is unconsciously visible. After the forests in Java were no longer able to be exploited, logging activities moved to Sumatra. Then after the forests in Sumatra are gone, they move to Kalimantan. Currently, the loss of stories about the splendor of forests in Kalimantan is only a matter of time. The pattern of deforestation is increasingly visible with the shift from the western region to #TimurIndonesia. Forest exploitation in the #TimurIndonesia region seems to have been very well prepared. More and more forest exploitation permits in the eastern region have been issued and have become land banking for large companies. There is no question if the natural forests in western Indonesia are no longer able to be converted into economic coffers. In line with FWI’s main campaign message in the future, it is very logical that the hashtag save #TimurIndonesia becomes the main message in every FWI effort to save natural forests in #TimurIndonesia from the modes of forest and land use permits that are increasingly structured even from the start the permit was proposed.

The hashtag #BukaInformasiHGU is closely related to FWI’s struggle to break the closed attitude of public agencies (Ministry of ATR / BPN). Since 2016, FWI has continued to voice so that HGU documents can be made public. The attitude of the Ministry of ATR / BPN which insists on closing HGU documents to the public on the grounds that these documents are prone to misuse, even to the point of opposing the Supreme Court’s decision is a step that has clearly violated the law. The high number of conflicts (Until 12 July 2019, 666 cases of conflict information entered into the KSP and 253 (53%) of them occurred in oil palm plantations) and the non-compliance of oil palm business actors (68% of oil palm land in Indonesia does not have HGUs with an area of 14, 8 million Ha) which underlies us to continue to fight for #BukaInformasiHGU.

Information disclosure is basically an entry point for the check & balance process, as a concrete form of public participation in monitoring government performance. Transparency is a means that must be provided for the public in order to carry out their duties in maintaining the pillars of democracy. Likewise in the management of natural resources and land, weak public oversight opens up opportunities for corruption and loss of state revenue. The increasingly closed community access to forestry operations also has implications for serious social conflicts.

Public information is information that is generated, stored, managed, sent, and / or received by a public body related to state administrators and / or administrators and the administration of other public bodies in accordance with the Law and other information relating to the interests. public. Meanwhile, what is meant by Public Bodies are executive, legislative, judicative and other bodies whose main functions and duties are related to state administration, whose funds part or all come from the state revenue and expenditure budget and / or regional revenue and expenditure budget, or organization. non-government, as long as part or all of the funds come from the state revenue and expenditure budget and / or regional revenue and expenditure budget, public donations, and / or abroad.

Land objects that are granted with Business Use Rights (HGU) are state lands. State land is land that is directly controlled by the state and there are no other rights on the land. If the land granted by HGU is state land which is a forest area, then the granting of the HGU can only be done after the status is revoked as a forest area. Likewise, if there are other rights on the land (for example: property rights), then the new HGU can be granted after the land rights are relinquished, so that the land in question becomes state land. This is in accordance with the provisions of Article 4 of Government Regulation no. 40 of 1996 concerning Business Use Rights, Building Use Rights, and Land Use Rights. Because HGU land is state land, HGU is closely related to the public interest, because state control over land is a manifestation of the mandate of the Indonesian people.

Therefore, the HGU document is closely related to the public interest, because state control over land is a manifestation of the mandate of the Indonesian people. In addition, although HGU can be granted to land with management rights and ownership rights, HGU holders still have special obligations while holding the HGU, where these obligations are closely related to the public interest. Thus, the public has the right to know and obtain information as a form of guarantee for the protection of their interests in accordance with the Purpose (Article 3) and the General Elucidation of Law No. 14 of 2008 concerning Freedom of Information (UU KIP).

So, the claim that the HGU document is prone to misuse is that if it is opened it is NOT RIGHT, because with #OpenInformasiHGU, we believe that efforts to resolve agrarian conflicts and overlapping permits can be resolved. So that FWI studies with HGU data on Kalimantan Island will be very useful in resolving this problem. With FWI continuing to encourage #BukaInformasiHGU efforts, this information is expected to make it easier for the public to see the current licensing status (legality) of oil palm plantation concessions, verify data, and make spatial analyzes related to land use in the oil palm plantation sector.

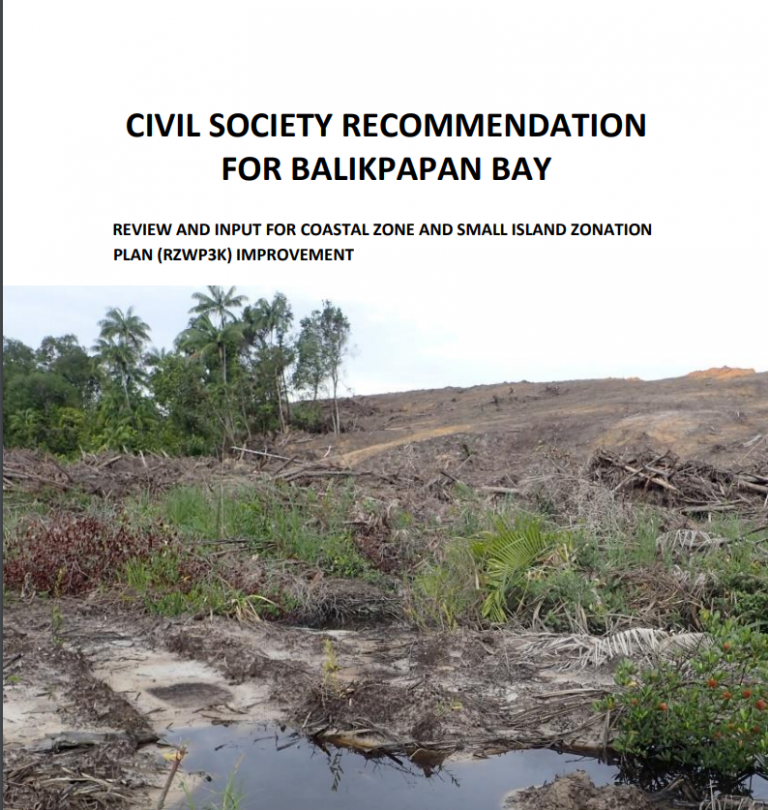

East Kalimantan is one of the provinces that stores forest resources and diversity of flora and fauna including marine biodiversity. Balikpapan Bay is one of the important seascapes in East Kalimantan Province. Ecologically, Balikpapan Bay has high biodiversity because it is the estuary of several rivers from 3 regencies / cities, namely Penajam Paser Utara Regency, Kutai Kartanegara Regency, and Balikpapan City which still have a wealth of mangrove ecosystems. Located in the south of the Mahakam Delta, the Balikpapan Bay mangrove ecosystem is a permanent habitat for several protected species such as proboscis monkeys (Nasalis Larvatus) (Toulec 2018), Pesut Pesut (Orcaella brevirostris) (Prayoga 2014), and Dugong (Dugong dugon) (RASI 2003 ). Several other important animal species such as the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) and Crocodile (Crocodilus sp.) Make Balikpapan Bay a feeding ground. The role of mangrove ecosystems is to become a habitat for various important protected animals because it provides a healthy environment and an abundant source of food. No wonder the mangrove ecosystem is also an important area for fishermen to catch fish (fishing ground) so that it becomes part of the living space for coastal communities. Balikpapan Bay mangrove ecosystem is an important area not only because of its ecological function, but also as a source of livelihood for coastal communities.

Based on the results of the 2018 FWI analysis, the area of natural forest cover in the mangrove ecosystem in Balikpapan Bay is around 16,831 hectares, which are spread along the downstream side of the river. The mangrove ecosystem in Balikpapan Bay is under threat due to the allocation of space in regional planning and the massive expansion of forest and land-based company concessions. Nearly 100 percent of the mangrove ecosystem area is in a cultivation function. And in the future, it can be ascertained that Balikpapan Bay will lose its mangrove ecosystem if the planning is actually carried out. Therefore, it is urgent to increase the protection status of the Balikpapan Bay mangrove ecosystem. On the other hand, it is necessary to integrate the National Strategy for Mangrove Ecosystem Management (SNPEM) in accordance with the mandate of Presidential Regulation Number 73 of 2012 concerning SNPEM into regional planning such as the East Kalimantan RTRW Regional Regulation, the Coastal Zone and Small Islands Zoning Plan (RZWP3K), Provincial and District Medium-Term Development (RPJMD), as well as the program plans of government agencies to be in line with national policy directives.

Status and Conservation Strategy of Mangrove Ecosystem In Balikpapan Bay East Kalimantan

Read More »Global climate change is predicted to affect coastal communities in various parts of the world. One of the things that will change is the acceleration of sea level rise which will cause further impacts such as submergence of small islands of land, increased flooding, coastal erosion, sea water intrusion and changes in ecological processes in coastal areas. Changes that occur will have an impact on the socio-economic aspects of coastal communities such as loss of infrastructure, decreasing ecological values, and economic values of coastal resources. Naturally, small islands are a vulnerable area, coupled with climate change, the vulnerability of small islands will increase.

As the largest archipelagic country in the world, the existence of small islands has an important value, both ecologically, economically, and is even able to maintain the sovereignty of the Indonesian nation over its territory. Indonesia has land on small islands which cover 12 million hectares. Of the land area in small islands, around 59% is still natural forest or an area of around 4.95 million hectares (FWI, 2017). Plus the area of Indonesia’s mangrove ecosystem which is the world’s contribution, namely 23 percent. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry stated that in 2015 the area of Indonesia’s mangrove ecosystem reached 3.48 million hectares.

The role of forest ecosystems in coastal areas and small islands should be taken into account. Its role is very important in mitigating global climate change. Mangrove ecosystems are able to store more carbon than most tropical forests even though they have a lower area. The existence of natural forests and mangroves in small islands is able to withstand the rate of sea water intrusion and maintain groundwater availability. However, now natural forests on small islands are increasingly under threat. This threat is caused by several factors, including exploitation of natural resources, difficulty in controlling natural resources in small islands, inappropriate zoning of forest area functions and rising sea levels.

What is worrying is that the destruction of natural forests on small islands cannot be separated from land-based investment activities such as HPH, HTI, plantations and mining. FWI’s 2013 search results found that an area of 1.4 million hectares or 20 percent of the land in small islands has been encumbered by land-based investment permits, such as HPH, HTI, oil palm plantations and mining. In fact, of all concessions on small islands, 60 percent of the land is still natural forest. Mining activities are the most massive threat with an area of 0.82 million hectares or 55 percent of the total investment activity in small islands. Followed by HPH (17 percent), oil palm (16 percent), and HTI (10 percent).

Exploitation of natural resources in coastal areas and small islands is clearly very threatening to the life of the nation and state. The existence of forest ecosystems on the coast and small islands is considered to be no less important in maintaining the sovereignty of the Indonesian nation as an archipelago. Nearly about 65 percent of Indonesia’s population occupies Indonesia’s coastal and marine areas. The notes of the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Nusantara (AMAN) stated that there are 30 million indigenous peoples in coastal areas and small islands. That number includes 10 million indigenous people who inhabit small islands in Indonesia. De facto, the lives of coastal communities and small islands are able to reach border areas which strengthen the legitimacy of the territory of the Republic of Indonesia.

Lack of attention and real action in protecting forests on small islands will have a negative impact on the community. The destruction of natural forests on small islands will deprive people of their livelihoods. In fact there will be no more life if the small islands sink. Relocation of communities whose areas are under threat is not a solution. Protection of forests in small islands must be carried out so that it does not diminish community rights to natural resources. On the basis of the above considerations, FWI with the message #SaveSmallIslands undertakes efforts to protect and save small islands in Indonesia from the pressure of exploitation of excessive natural resources (extractive industries) and spatial planning of small islands that are considered wrong.