In the last five years, Central Halmahera has frequently experienced flooding. Based on a compilation data from media and the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), there has been approximately 19 floods recorded in Weda Bay of Central Halmahera from 2019 to July 2024 due to nickel mining. Most recently, on 28th July 2024, floods struck several villages in Central Weda District after heavy rain for two days. Kobe River overflowed, flooding residential area in some villages. The worst conditions of this flood occured in Luko Lamo and Lelilef Village, with water level reaching almost two meters. Strong currents severed the main road of Trans Weda – Waleh, paralyzing residents of the two villages completely.

The heavy rainfall often becomes the scapegoat for the occurrence of flooding. However, floods are a part of hydrometeorology disasters that are correlated with the weather conditions such as temperature, wind, moisture, and hydrology cycle. Additionally, anthropogenic activities have a significant influence on intensity and frequency of hydrometeorology disasters. Deforestation or forest cover loss also contribute to the rise of local temperatures and water vapor concentration in the atmosphere. The loss of vegetation also heightens the chance of erosion and water runoff, as the land loses it’s capacity for absorption, elevating the of flooding and landslides.

A study from Forest Watch Indonesia (FWI) shows that the decrease in forest cover is directly associated with the increased flood risk. An analysis that compares forest cover ratio data with flood risk from the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) indicate a clear trend of correlation: areas with low forest cover have higher probability of flood, whilst areas with higher forest cover have lower probability. This finding is supported by a study that conducted by Bradshaw (2007), which found a positive relation between deforestation and the frequency of global floods during the period from 1990 to 2000.

The Weda Bay area in Central Halmahera has undergone significant changes in the past five years. Expansion of the nickel downstream industrial zone has accelerated due to the policy banning the export of low-grade nickel through the Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Regulation No. 11 of 2019 and Presidential Regulation No. 55 of 2019. The Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP), an integrated industrial zone for nickel processing and electric vehicle (EV) battery component production, has now become a National Strategic Project (PSN) officially launched by President Joko Widodo through Presidential Regulation No. 109 of 2020. At this moment, the operational area of IWIP has reached 4.000 hectares.

The development of this industrial zone aligns with the increasing global demand for nickel. Currently, the major of nickel is used in the stainless steel industry (approximately 74%) and 5-8% are for batteries. Nonetheless, the demand for nickel in batteries is expected to continue rising as the EV market grows. The International Energy Agency projects that annual demands of grade 1 nickel could reach 925 kilotons per year by 2030 under the stated policies scenario, and up to 1.900 kilotons per year under the sustainable development scenario. Indonesia itself has the largest nickel resources in the world, totalling 72 million tons or 525 of global nickel stock. In 2022, Indonesia’s nickel ore production reached 1,6 million tons, the highest in the world, surpassing Philippines, which produced arround 330.000 tons.

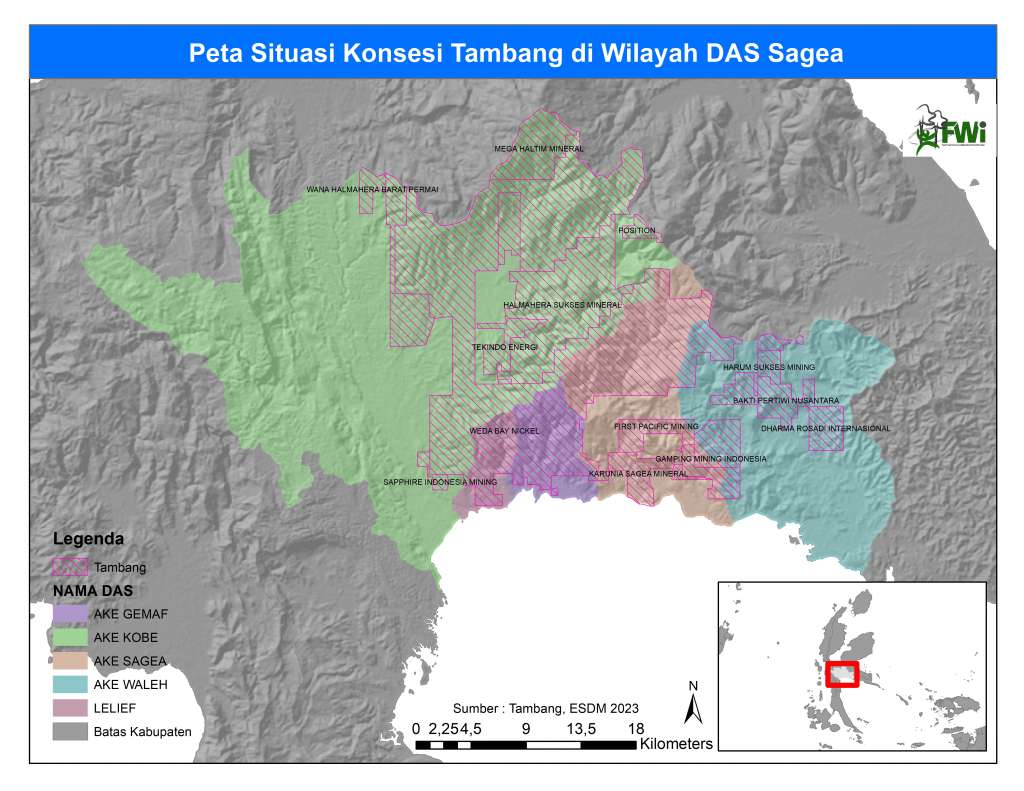

According to data from the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources up to 2023, there are 13 mining business licenses (IUP) covering a total concession area of 59,678.04 hectares in Central Halmahera, predominantly for nickel, and most are already begun operating. However, nickel mining operations and processing have caused environmental damage that adversely affects local communities. The impacts include deforestation, river and ocean pollution, and the destruction of residents’ living spaces. One example is the pollution of the Sagea River in the villages of Sagea and Kiya, North Weda District, since 2023. Mining activities upstream are believed to be causing the water to turn brownish-yellow, with thick sediment, forcing communities to bear the consequences.

Based on these conditions, FWI conducted a study to identify the environmental impacts of mining activities and nickel downstream industrialization in Central Halmahera. The study includes an analysis of the increased flood potential caused by land cover changes, as well as projections of its impacts on the socio-economic conditions of the community. The results of this study are expected to provide policy recommendations and mitigation measures to minimize the negative impacts of mining activities and nickel downstream industrialization.

METHODOLOGY

This study uses a spatial-temporal modeling approach, which combines spatial and temporal data to analyze flood potential related to land clearing due to mining activities. The scope of the study encompasses five river basin (DAS) in Weda Bay area: Ake Kobe, Ake Sagea, Lelilef, Ake Gemaf, and Ake Waleh, covering a total area of 129.970, 54 hectares. In most of these river basin, companies have obtained active mining business licences (IUP) that have already started operating (Figure 1).

Flood Risk Analysis

This flood potential analysis is conducted using the Flood Hazard Index (FHI) method. FHI is a multi-parameter model based on Geographic Information System (GIS) used to identify areas at risk of flooding on a regional scale (Kazakiz et al., 2015). The analyzed data includes the years 2016, 2019, and 2024. The year 2016 represents the condition before massive mining activities, 2019 reflects the period during the development of the IWIP industrial area, and 2024 indicates the time when industrial and mining activities are operating at high intensity.

The FHI value is calculated based on the weights of each flood-causing factor, which include rainfall, land cover, flow accumulation, land slope, topography, river buffer, and geology. Five of these seven parameters are fixed, while the other two, land cover and rainfall anomalies, are dynamic.

Rainfall anomalies are analyzed using the Fournier Index (MFI), which indicates the variability and aggressiveness of rainfall and its impact on soil erosion (Munka et al., 2007). A higher MFI value indicates a greater level of rainfall aggressiveness. The data used in the MFI analysis comes from CHIRPS V.2 (Climate Hazards InfraRed Precipitation with Station data Version 2.0) for the years 2016, 2019, and 2024 (up to July).

Land cover analysis is conducted using a machine learning algorithm called random forest, utilizing a combination of Sentinel 2-A satellite imagery and Planet Basemaps with a final resolution of 5 meters. Land cover data is analyzed for the years 2016, 2019, and 2024, and this process is performed using a cloud computing platform (Aulia et al., 2022).

Analysis of Flood Impact Projections on the Socio-economic Conditions of Communities

The results of the flood hazard potential analysis are used to project the possible impacts of flooding. This projection includes social, economic, and infrastructure impacts. Social impacts are analyzed based on the number of people and households living in high-risk areas. Economic impacts are calculated using agricultural land cover data from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in 2022. Meanwhile, the impact on infrastructure is analyzed by mapping road data from the RBI (Base Map) of the Geospatial Information Agency overlaid with flood risk areas.

Economic loss estimation is conducted using the ECLAC (DaLA) method, which is generally used in Latin America and the Caribbean but can also be applied to flood disasters in Asia (Jayantara, 2020). This calculation involves multiplying the affected area or the number of impacted units by the replacement unit value, then multiplying by a damage factor assumed to be 1 in this study.

Aziz Fardhani Jaya

Eryana Nurwenda Az-Zahra

Rosima Wati Dewi

Data Analyst & Map Presenter:

Ogy Dwi Aulia

Eryana Nurwenda Az-Zahra

Rosima Wati Dewi

Andi Juanda

Layout & Design:

S Utamidata