Indonesia is home to some of the Earth’s most biodiverse and carbon-rich forests, and 50 to 70 million Indigenous people who rely on these intact ecosystems for their survival. Yet burning wood in biomass power or “co-fired” in coal power plants could bring Indonesia’s forests to an “irreversible point” by 2040. Carbon reduction policies that divert public dollars from solar and wind into biomass energy threaten forests and biodiversity across Southeast Asia.

A letter signed by more than 500 scientists and economists in 2021 warned that the European Commission’s mandate to increase renewable energy by 20% and treat biomass as a carbon neutral power source would “create a model that encourages tropical countries to cut more of their forests.”

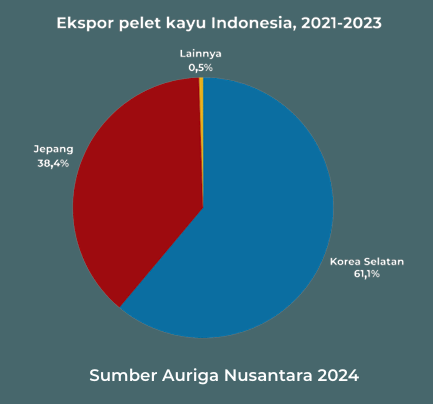

Three years later, their prediction is unfolding across Southeast Asia. Last year, South Korea and Japan were the primary actors driving growth in global demand for wood pellets. In 2023, Asia experienced 20% year-on-year growth in wood pellet demand, led by Japan and South Korea. In 2022, Japan and South Korea imported the most wood pellets outside of Europe with 4.4 million tonnes and 3.9 million tonnes, respectively.

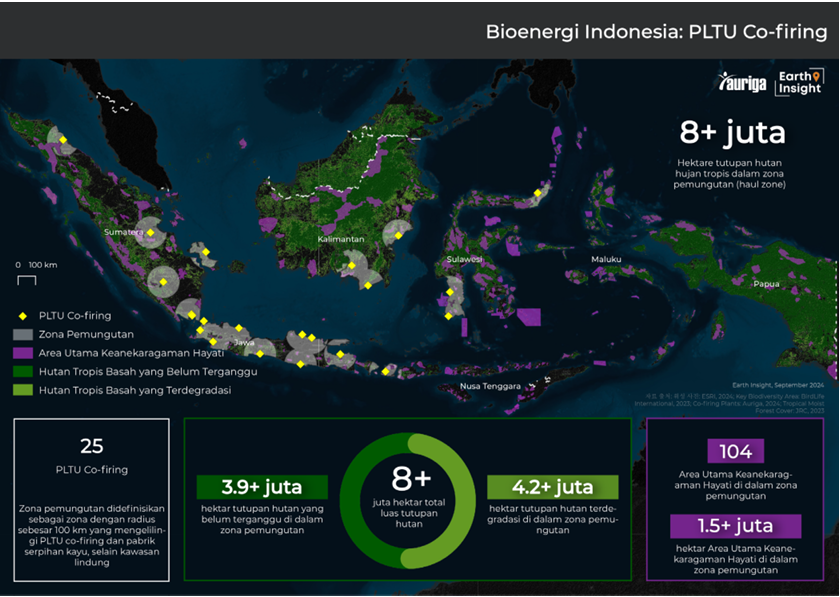

Their dire warning is illustrated in this preliminary assessment of threats to Indonesia’s forests from co-firing coal plants, energy plantation forest concessions, and wood chip and pellet mill haul zones. Under Indonesia’s energy transition plans, biomass will generate 19.7TWh by 2025, the majority of which (64.5%) will come from co-firing in coal plants. Forests designated as “energy plantations” are expected to supply half of what is needed. The country’s forests face unprecedented threats from the industrial scale projected for biomass demand.

Burning wood for energy in Indonesia, Japan and South Korea is a threat to bio-diverse tropical forests across Southeast Asia.

Subsidy programs in South Korea and Japan have radically expanded demand and production of wood pellets and chips from forests across Southeast Asia.

An analysis of wood pellet imports found a direct causal relationship between Southeast Asian wood pellet production and South Korea’s renewable energy policy. From 2012 to 2021, Vietnam’s total wood pellet production grew from 50 thousand tonnes to 3.5 million tonnes; Malaysia’s production jumped from 40 thousand tonnes to 710.0 thousand tonnes, while Indonesia’s production increased from 20 thousand tonnes to 330 thousand tonnes. Additional power plant capacity is expected to make Japan the largest wood pellet consumer in the world.

Deforestation Threats from Wood Energy in Indonesia

Wood pellet demand in South Korea and Japan is spurring a fast-growing, nascent forest energy industry in Indonesia. As seen in the graph below, the two countries combined bought more than 99% of Indonesia’s wood pellet exports from 2021 to 2023. In this time frame, Indonesia’s wood pellet exports to South Korea jumped from 49.8 tonnes to 68,025.1 tonnes; exports to Japan rose from 54 tonnes to 52,734.7 tonnes.

Indonesia’s 10% co-firing mandate poses a threat to 10 million hectares of undisturbed cover in wood chip and pellet haul zones. It is estimated that using wood for a 10% reduction in coal at Indonesia’s largest power plants could trigger the deforestation of an area roughly 35 times the size of Jakarta — resulting in CO2 emissions almost five hundred times higher than current levels. This year, six power plants (Paiton 1 & 2, Indramayu, Rembang, Ropa, and Adipala) used wood pellets; another four (Anggrek, Bolok, Tembilahan, and Tarahan) burned wood chips. The country’s 2021-2030 electricity strategy projects demand for 8.05 million tonnes of biomass for co-firing by 2030. New power plants are being designed to burn up to 30% biomass.

Energy Plantation Forest

In order to meet projected domestic and foreign demand for woody biomass, forest energy “estates” have emerged as another industrial pressure on forests that need restoration and protection. Our estimates show that there are currently more than 400,000 hectares of undisturbed tropical forest in more than 1.2 million hectares of energy plantation forests in Indonesia. These threats could expand drastically, unless different energy transition pathways are chosen. Meeting the country’s co-firing mandate could require 10.23 million tonnes of wood pellets a year an area equivalent to 3.27 million football fields potentially driving deforestation rates as high as 2.1 million hectares a year.