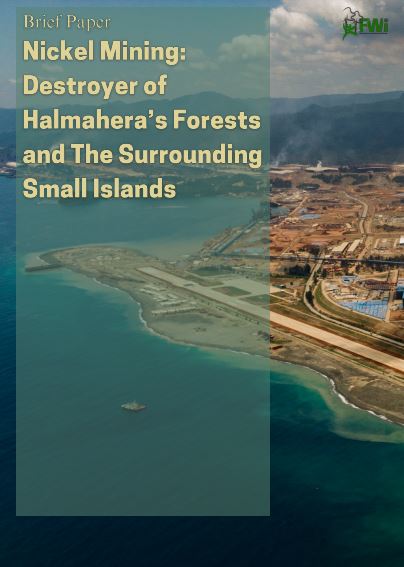

Five years ago, before nickel mining in Indonesia was given the “red carpet”, Halmahera was a peaceful, cool place with good environmental quality to fulfill people’s basic right to live a better life. In contrast, at the end of September 2023, after the Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) complex was built, which has cost at least 11 billion USD, various problems emerged such as environmental crises, pollution, damage to natural resources, loss of forests and biodiversity habitats, and the living space of indigenous tribes were taken away. Now, the industrial complex that stretches about 9 kilometers requires at least up to 300 thousand tons of nickel per year which are divided into 30 Rotary Klein Electric Furnace (RKEF) smelters. Of course, this has consequences for the availability of forest and land areas in Halmahera.

In aggregate, Halmahera and its surrounding small islands have been encumbered by 201,000 hectares of nickel mining licenses divided into 43 concessions. Nearly 90% or around 180,000 hectares are located in protected and production forest areas. Mining has exclusivity even though its very existence threatens natural forests and the existence of indigenous peoples and local communities. Although Halmahera and its surrounding small islands are known to have the highest diversity of flora and even vegetation types in the world[1].

"The Red Carpet" of Nickle Mining

The consequences of nickel downstreaming in Indonesia have significant impacts on forests and the living space of indigenous peoples and local communities. Mining policies are given discretion without area restrictions and even ease in licensing.

No Limitation on Mining Concession Area

Mining businesses including nickel that are connected to the downstream or smelter industry are free to obtain approval and conduct mining operations in all areas or regions. The Minister, in this case, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, has the right to grant approval for the use of forest areas to mining companies without having to consider the adequacy of forest area in one watershed, in one forest area function, even including small islands. This is as regulated in Permen LHK Number 7 of 2021 (article 372) as a derivative policy of the Job Creation Law. The nickel mining business is like a National Strategic Project, all issues related to social and environmental interests caused by an impact can be put aside as long as the project can run and does not hamper investment. In general, mining not connected to the downstream industry and not PSN is limited to a maximum of 10%.

Centralized Licensing Without Regional Control

Apart from the MoEF providing regional resources for nickel mining, regulations on the mining industry are under the authority of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM). Since 2020, when all licensing authority was withdrawn to the central government, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources has over power to manage mining licenses in Indonesia. At least recorded after 2020, it manages thousands of mining licenses that have caused many environmental problems. ESDM handles all issues related to mineral and coal management ranging from licensing, supervision, environmental impact, and law enforcement. This has caused overlapping licenses in forest and land governance. There is even no room for local governments to determine that mining licenses are revoked even though they are proven to destroy forests and harm surrounding communities.

The difficulty in unraveling licensing issues is part of how ESDM protects mining business companies that have contributed most of the state’s income. ESDM needs to protect businesses that generate a lot of income for the state through various instruments such as ease of bureaucracy and smooth business. So the policies issued then benefit the interests of a few people more than saving the lives of the wider community.

The concept of Regulatory Capture (Reg Capture) is a phenomenon that occurs when a state agency established to act in the public interest, instead prioritizes the commercial or political interests of a special interest group and dominates an industry or sector where the agency is located. When the regulation is issued, the interests of the company or political group are prioritized or favored over the interests of society[i].

Administrative Sanctions for Forest Destroyers

The issue of environmental protection can be relegated to the back burner, even for mining companies that were previously fined Rp 10 billion and sentenced to 5 years in prison for not having a Borrow-to-Use Forest Area Permit (IPPKH). After the Job Creation Law, companies destroying forests without permits will only be subject to administrative sanctions in the form of fines (Articles 36 and 37 of the Job Creation Law). The law, which is actually the realization of the stipulation of government regulations in lieu of law number 2 of 2022 concerning job creation, is the main entrance to ease investment in Indonesia, including the mining sector. Even worse, derivative regulations of the UUCK such as PP 22/2021 also allow mines to dispose (dumping) B3 waste into environmental media such as the sea as long as they get approval from the central government. Mining business activities are regulated in such a way that there is minimal public control. Civil society involvement is limited in the preparation of AMDAL in the Job Creation Law. Whereas the process of community involvement in AMDAL and environmental permits is needed to carry out checks and balances to ensure the implementation of community rights and obligations in the field of environmental protection and management, as well as to realize the implementation of a transparent, effective, accountable and quality environmental permit process.

No role for local government

Since its revision in 2020, Law No. 3 of 2020 on minerals and coal regulates many provisions that reduce the authority of local governments and community participation in areas/locations around mines. In addition to the authority of local governments being withdrawn to the center, such as local governments no longer having the power to revoke mining permits that commit violations in their area, this policy also does not provide channels for complaints by the community. In fact, as in many cases involving communities in the mining vicinity, if there is a rejection, it will usually lead to criminalization (Article 162: fines or crimes for those who refuse legal mining permits).

Lack of Mine Pit Reclamation Obligation

The concessions provided by the policy of Law number 3 of 2020 concerning mineral and coal also cover aspects of environmental responsibility by mining companies, one of which is the obligation to reclaim mining pits. Article 99 paragraph 3 in the Minerba Law states that companies are only obliged to close mining pits based on the percentage determined by laws and regulations. As a result of this, jatam data in East Kalimantan recorded 40 victims (2011-2021) due to drowning in mining pits that were not reclaimed[i]. Mining companies that are proven to be negligent and do not carry out post-mining reclamation obligations are also guaranteed to be able to extend their license contracts for 2 times 10 years.